A Stamp of Approval for Electric Vehicles?

Ross Marchand

April 6, 2022

Inspector general (IG) reports can be eye-opening reads, detailing how government programs are wasting millions or even billions of taxpayer dollars. IG reports can also provide a valuable service for policymakers by highlighting how different agency decisions can make large impacts on government spending.

One recent example is the recent United States Postal Service (USPS) IG report on electric vehicles (EVs), which runs through different scenarios on agency EV use with detailed cost and mileage assumptions. Unfortunately, the report’s findings have been repeatedly mischaracterized. According to CleanTechnica contributor Steve Hanley, the report, “states nearly 99% of all postal delivery routes within the United States could be served reliably by battery-powered vehicles and that they would cost less to buy, fuel, and maintain than a conventional vehicle over their projected 20-year useful life.” The Washington Post’s “agency alert” on the report also emphasized the upsides of EVs, without mentioning that overall, 20-year EV ownership costs were found to be higher than for a gas-powered fleet. As detailed below, the USPS IG presents a nuanced view of EV purchases that doesn’t track neatly onto media reports.

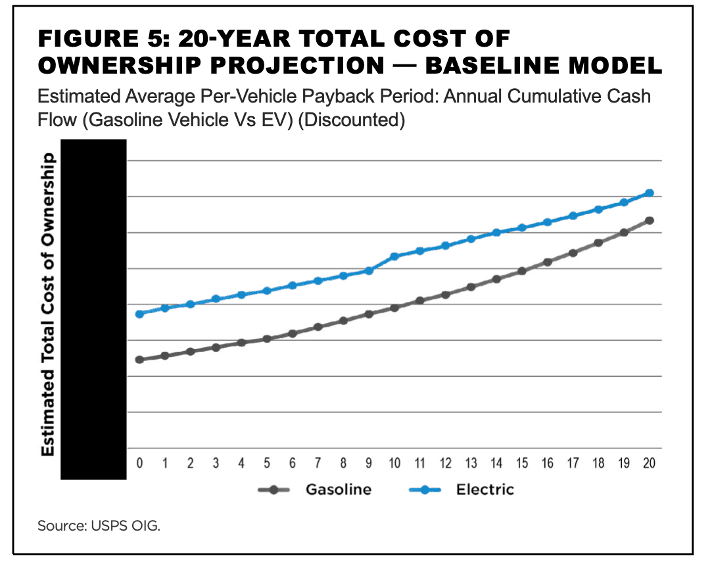

Baseline Scenario: EVs cost more

As shown in the above chart found on page 9 of the IG report, an EV fleet would be more expensive than conventional trucks assuming, “an average delivery route length of 24 miles per day, and 301 operating days per year.” The key here is that EVs are approximately 11 percent more expensive up-front than their conventional counterparts, with cost recoupment possible down the road via reduced energy and maintenance costs. Down-the-road costs are discounted using a 2.2 percent interest rate, reflecting the common, reasonable assumption among regulators and financial analysts that a dollar held today is worth more than a dollar held tomorrow.

Even these assumptions may be too generous to electric vehicles. On page 7 of the report, the IG states, “[e]lectric vehicles are generally more mechanically reliable than gas-powered vehicles and would require less scheduled maintenance and reduced maintenance costs.” But, according to an in-depth analysis by analytical firm We Predict, “in a three-month time frame, EV service costs were 2.3 times higher than a gasoline-powered car. At 12 months, EV service costs were still 1.6 times higher. We Predict found service-related costs averaged $306 per electric vehicle, while a gas-powered car averaged $189.” Therefore, the assumption that EVs have fewer moving parts and therefore cost less post-purchase may not necessarily be true.

The IG notes that there are some scenarios where 20-year total ownership costs could be lower for EVs than gas-powered trucks, but only if we assume that, “electric vehicles have lower fuel and maintenance costs per mile.” And, even then, EVs would make sense on less than 10 percent of mail routes (in the 40–70-mile range). Finally, the IG notes that EV costs could be lower than gas-powered costs if Congress sufficiently subsidized EV adaption. This, of course, ignores the fact that any federal subsidies would impose real costs on taxpayers and don’t actually lower the underlying expenses associated with EVs.

Chargers

According to the IG (on page 5), EV charging technology purchases are filled with tradeoffs: “Level 1 charging would require the least investment in new infrastructure but is the slowest, with vehicles needing 11 to 20 hours to fully charge. Level 2 charging is more expensive than level 1 but can typically fully charge a battery within eight hours. Direct current fast charging is much faster but significantly more expensive to own and operate.” The watchdog believes that level 2 charging would work for most postal vehicles, since it, “would allow all batteries to be fully charged during the 14 hours that a delivery vehicle generally sits in the lot (from 6:00 PM to 8:00 AM).”

This becomes an issue, though, when carriers are returning from their routes past 6 PM. One USPS audit of the Bay Valley (CA) District noted that, “in the heart of the nation’s ecommerce hub — found that carriers and CCAs fell short of the 100 percent goal by 6 p.m. In calendar year 2016, only 75 percent of carriers returned to the office by 6 p.m.” More recent audits centered around other districts across the country have similarly worrying results.

Finally, there’s a dispute between the IG and the USPS about how EV chargers are priced into cost projections. The IG, “acknowledges that its projections of charger equipment and installation costs differ from the Postal Service’s own estimates and that the Postal Service considers these to be underestimates.” It’s likely that the USPS has a better handle on procurement and make-work costs, given that the agency is “closer to the action” in doing these things than the IG is. It’s important that USPS management and the IG work to reconcile these differing projections.

Why does this statistical hoopla matter?

Even though the USPS spurned an EV truck supplier in building the next generation of postal vehicles, EVs seem to be very much on the agency’s mind. The USPS’ recently placed first order for Next Generation Delivery Vehicles includes a minimum of 10,019 battery electric vehicles instead of 5,000 EVs as originally planned. The agency also noted that they are prepared to further increase EV purchases “should additional funding become available from internal or other sources…” In other words, the USPS is using the prospect of EV purchases as a bargaining chip for more taxpayer dollars. That would be a recipe for disaster at a time of surging federal red ink and out-of-control inflation. Policymakers should do the right thing and pay close attention to this IG report.

Ross Marchand is a senior fellow for the Taxpayers Protection Alliance.